Blood viscoelasticity

Blood Viscoelasticity is a property of human blood that is primarily due to the elastic energy that is stored in the deformation of red blood cells as the heart pumps the blood through the body. The energy transferred to the blood by the heart is partially stored in the elastic structure, another part is dissipated by viscosity, and the remaining energy is stored in the kinetic motion of the blood. When the pulsation of the heart is taken into account, an elastic regime becomes clearly evident. It has been shown that the previous concept of blood as a purely viscous fluid was inadequate since blood is not an ordinary fluid. Blood can more accurately be described as a fluidized suspension of elastic cells.

Contents |

History

In early theoretical work, blood was treated as a non-Newtonian viscous fluid. Initial studies had evaluated blood during steady flow and later, using oscillating flow.[1] Professor George B. Thurston, of the University of Texas, first presented the idea of blood being viscoelastic in 1972. The previous studies that looked at blood in steady flow showed negligible elastic properties because the elastic regime is stored in the blood during flow initiation and so its presence is hidden when a flow reaches steady state. The early studies used the properties found in steady flow to derive properties for unsteady flow situations.[2][3] Advancements in medical procedures and devices required a better understanding of the mechanical properties of blood.

Viscoelasticity of Blood

The red blood cells occupy about half of the volume of blood and possess elastic properties. This elastic property is the largest contributing factor to the viscoelastic behavior of blood. The large volume percentage of red blood cells at a normal hematocrit level leaves little room for cell motion and deformation without interacting with a neighboring cell. Calculations have shown that the maximum volume percentage of red blood cells without deformation is 58% which is in the range of normally occurring levels.[4] Due to the limited space between red blood cells, it is obvious that in order for blood to flow, significant cell to cell interaction will play a key role. This interaction and tendency for cells to aggregate is a major contributor to the viscoelastic behavior of blood. Red blood cell deformation and aggregation is also coupled with flow induced changes in the arrangement and orientation as a third major factor in its viscoelastic behavior.[5][6] Other factors contributing to the viscoelastic properties of blood is the plasma viscosity, plasma composition, temperature, and the rate of flow or shear rate. Together, these factors make human blood viscoelastic, non-Newtonian, and thixotropic.[7]

When the red cells are at rest or at very small shear rates, they tend to aggregate and stack together in an energetically favorable manner. The attraction is attributed to charged groups on the surface of cells and to the presence of fibrinogen and globulins.[8] This aggregated configuration is an arrangement of cells with the least amount of deformation. With very low shear rates, the viscoelastic property of blood is dominated by the aggregation and cell deformability is relatively insignificant. As the shear rate increases the size of the aggregates begins to decrease. With a further increase in shear rate, the cells will rearrange and orient to provide channels for the plasma to pass through and for the cells to slide. In this low to medium shear rate range, the cells wiggle with respect to the neighboring cells allowing flow. The influence of aggregation properties on the viscoelasticity diminish and the influence of red cell deformability begins to increase. As shear rates become large, red blood cells will stretch or deform and align with the flow. Cell layers are formed, separated by plasma, and flow is now attributed to layers of cells sliding on layers of plasma. The cell layer allows for easier flow of blood and as such there is a reduced viscosity and reduced elasticity. The viscoelasticity of the blood is dominated by the deformability of the red blood cells.

Modeling Viscoelasticity of Blood

Maxwell Model

If a small cubical volume of blood is considered, with forces being acted upon it by the heart pumping and shear forces from boundaries. The change in shape of the cube will have 2 components:

- Elastic deformation which is recoverable and is stored in the structure of the blood.

- Slippage which is associated with a continuous input of viscous energy.

When the force is removed, the cube would recover partially. The elastic deformation is reversed but the slippage is not. This explains why the elastic portion is only noticeable in unsteady flow. In steady flow, the slippage will continue to increase and the measurements of non time varying force will neglect the contributions of the elasticity.

Figure 1 can be used to calculate the following parameters necessary for the evaluation of blood when a force is exerted.

-

-

- Shear Stress:

- Shear Stress:

-

-

-

- Shear Strain:

- Shear Strain:

-

-

-

- Shear Rate:

- Shear Rate:

-

A sinusoidal time varying flow is used to simulate the pulsation of a heart. A viscoelastic material subjected to a time varying flow will result in a phase variation between  and

and  represented by

represented by  . If

. If  , the material is a purely elastic because the stress and strain are in phase, so that the response of one caused by the other is immediate. If

, the material is a purely elastic because the stress and strain are in phase, so that the response of one caused by the other is immediate. If  = 90°, the material is a purely viscous because strain lags behind stress by 90 degrees. A viscoelastic material will be somewhere in between 0 and 90 degrees.

= 90°, the material is a purely viscous because strain lags behind stress by 90 degrees. A viscoelastic material will be somewhere in between 0 and 90 degrees.

The sinusoidal time variation is proportional to  . Therefore the size and phase relation between the stress, strain, and shear rate are described using this relationship and a radian frequency,

. Therefore the size and phase relation between the stress, strain, and shear rate are described using this relationship and a radian frequency,  were

were  is the frequency in Hertz.

is the frequency in Hertz.

-

-

- Shear Stress:

- Shear Stress:

-

-

-

- Shear Strain:

- Shear Strain:

-

-

-

- Shear Rate:

- Shear Rate:

-

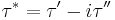

The components of the complex shear stress can be written as:

Where  is the viscous stress and

is the viscous stress and  is the elastic stress. The complex coefficient of viscosity

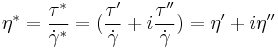

is the elastic stress. The complex coefficient of viscosity  can be found by taking the ratio of the complex shear stress and the complex shear rate[9]:

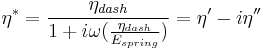

can be found by taking the ratio of the complex shear stress and the complex shear rate[9]:

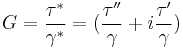

Similarly, the complex dynamic modulus G can be obtained by taking the ratio of the complex shear stress to the complex shear strain.

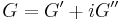

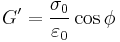

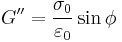

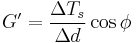

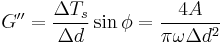

Relating the equations to common viscoelastic terms we get the storage modulus,G', and the loss modulus,G".

A viscoelastic Maxwell material model is commonly used to represent the viscoelastic properties of blood. It uses purely viscous damper and a purely elastic spring connected in series. Analysis of this model gives the complex viscosity in terms of the dashpot constant and the spring constant.

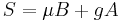

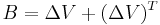

Oldroyd-B model

One of the most frequently used constitutive models for the viscoelasticity of blood is the Oldroyd-B model. There are several variations of the Oldroyd-B non-Newtonian model characterizing shear thinning behavior due to red blood cell aggregation and dispersion at low shear rate. Here we consider a three-dimensional Oldroyd-B model coupled with the momentum equation and the total stress tensor.[10] A non Newtonian flow is used which insures that the viscosity of blood  is a function of vessel diameter d and hematocrit h. In the Oldroyd-B model, the relation between the shear stress tensor B and the orientation stress tensor A is given by:

is a function of vessel diameter d and hematocrit h. In the Oldroyd-B model, the relation between the shear stress tensor B and the orientation stress tensor A is given by:

![S %2B \gamma \left[ \frac{DS}{Dt}- \Delta V \cdot S-S \cdot{(\Delta V)}^T \right]= \mu (h,d) \left[ B %2B \gamma \left( \frac{DB}{Dt}- \Delta V \cdot B - B \cdot {(\Delta V)}^T \right) \right] - gA %2B C_1\left(gA - \frac {C_2I}{\mu (h,d)^2} \right)](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/dfff5b95578c194d0c1ce6b62c96d59b.png)

where D/Dt is the material derivative, V is the velocity of the fluid, C1, C2, g,  are constants. S and B are defined as follows:

are constants. S and B are defined as follows:

Viscoelasticity of Red Blood Cells

Red blood cells are subjected to intense mechanical stimulation from both blood flow and vessel walls, and their rheological properties are important to their effectiveness in performing their biological functions in the microcirculation.[11] Red blood cells by themselves have been shown to exhibit viscoelastic properties. There are several methods used to explore the mechanical properties of red blood cells such as:

-

-

- micropipette aspiration[12]

- micro indentation

- optical tweezers

- high frequency electrical deformation tests

-

These methods worked to characterize the deformability of the red blood cell in terms of the shear, bending, area expansion moduli, and relaxation times.[13] However, they were not able to explore the viscoelastic properties. Other techniques have been implemented such as photoacoustic measurements. This technique uses a single-pulse laser beam to generate a photoacoustic signal in tissues and the decay time for the signal is measured. According to the theory of linear viscoelasticity, the decay time is equal to the viscosity-elasticity ratio and therefore the viscoelasticity characteristics of the red blood cells could be obtained.[14]

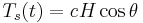

Another experimental technique used to evaluate viscoelasticity consisted of using ferriomagnetic beads bonded to a cells surface. Forces are then applied to the magnetic bead using optical magnetic twisting cytometry which allowed researchers to explore the time dependent responses of red blood cells.[15]

is the mechanical torque per unit bead volume (units of stress) and is given by:

is the mechanical torque per unit bead volume (units of stress) and is given by:

where H is the applied magnetic twisting field,  is the angle of the bead’s magnetic moment relative to the original magnetization direction, and c is the bead constant which is found by experiments conducted by placing the bead in a fluid of known viscosity and applying a twisting field.

is the angle of the bead’s magnetic moment relative to the original magnetization direction, and c is the bead constant which is found by experiments conducted by placing the bead in a fluid of known viscosity and applying a twisting field.

Complex Dynamic modulus G can be used to represent the relations between the oscillating stress and strain:

where  is the storage modulus and

is the storage modulus and  is the loss modulus:

is the loss modulus:

where  and

and  are the amplitudes of stress and strain and

are the amplitudes of stress and strain and  is the phase shift between them.

is the phase shift between them.

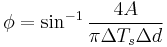

From the above relations, the components of the complex modulus are determined from a loop that is created by comparing the change in torque with the change in time which forms a loop when represented graphically. The limits of  - d(t) loop and the area, A, bounded by the

- d(t) loop and the area, A, bounded by the  - d(t) loop, which represents the energy dissipation per cycle, are used in the calculations. The phase angle

- d(t) loop, which represents the energy dissipation per cycle, are used in the calculations. The phase angle  , storage modulus G', and loss modulus G then become:

, storage modulus G', and loss modulus G then become:

where d is the displacement.

The hysteresis shown in figure 3 represents the viscoelasticity present in red blood cells. It is unclear if this is related to membrane molecular fluctuations or metabolic activity controlled by intracellular concentrations of ATP. Further research is needed to fully explore these interaction and to shed light on the underlying viscoelastic deformation characteristics of the red blood cells.

Effects of Blood Vessels

When looking at viscoelastic behavior of blood in vivo, it is necessary to also consider the effects of arteries, capillaries, and veins. The viscosity of blood has a primary influence on flow in the larger arteries, while the elasticity, which resides in the elastic deformability of red blood cells, has primary influence in the arterioles and the capillaries.[16] Understanding wave propagation in arterial walls, local hemodynamics, and wall shear stress gradient is important in understanding the mechanisms of cardiovascular function. Arterial walls are anisotropic and heterogeneous, composed of layers with different bio-mechanical characteristics which makes understanding the mechanical influences that arteries contribute to blood flow very difficult.[17]

Medical Reasons for Better Understanding

From a medical standpoint, the importance of studying the viscoelastic properties of blood becomes evident. With the development of cardiovascular prosthetic devices such as heart valves and blood pumps, the understanding of pulsating blood flow in complex geometries is required. A few specific examples are the effects of viscoelasticity of blood and its implications for the testing of a pulsatile Blood Pumps.[18] Strong correlations between blood viscoelasticity and regional and global cerebral blood flow during cardiopulmonary bypass have been documented.[19]

This has also led the way for developing a blood analog in order to study and test prosthetic devices. The classic analog of glycerin and water provides a good representation of viscosity and inertial effects but lacks the elastic properties of real blood. One such blood analog is an aqueous solution of Xanthan gum and glycerin developed to match both the viscous and elastic components of the complex viscosity of blood.[20]

Normal red blood cells are deformable but many conditions, such as sickle cell disease, reduce their elasticity which makes them less deformable. Red blood cells with reduced deformability have increasing impedance to flow, leading to an increase in red blood cell aggregation and reduction in oxygen saturation which can lead to further complications. The presence of cells with diminished deformability, as is the case in sickle cell disease, tends to inhibit the formation of plasma layers and by measuring the viscoelasticity, the degree of inhibition can be quantified.[21]

See also

References

- ^ J. Womersley, Method for Calculation of Velocity, Rate of Flow and Viscous Drag in Arteries when the Pressure Gradient is Known, Amer. Journal Physiol. 1955, 127, 553-563.

- ^ G. Thurston, Viscoelasticity of human blood, Biophysical Journal, 1972, 12, 1205–1217.

- ^ G. Thurston, The Viscosity and Viscoelasticity of Blood in Small Diameter Tubes, Microvascular Research, 1975, 11, 133-146.

- ^ A. Burton, Physiology and Biophysics of Circulation, Year Book Medical Publisher Inc., Chicago, 1965, p. 53.

- ^ G. Thurston and Nancy M. Henderson, Effects of flow geometry on blood Viscoelasticity, Biorheology 2006, 43, 729–746

- ^ G. Thurston, Plasma Release – Cell Layering Theory for Blood Flow, Biorheology 1989, 26, 199–214

- ^ G. Thurston, Plasma Rheological Parameters for the Viscosity, Viscoelasticity, and thixotropy of Blood, Biorheology 1979, 16, 149–162

- ^ L. Pirkl and T. Bodnar, Numerical Simulation of Blood Flow Using Generalized Oldrroyd-B Model, European Conference on Computational Fluid Dynamics, 2010

- ^ T. How, Advances in Hemodynamics and Hemorheology Vol. 1, JAI Press LTD., 1996, 1-32.

- ^ R. Bird, R. Armstrong, O. Hassager, Dynamics of Polymeric Liquids; Fluid Mechanic, 1987, 2, 493 - 496

- ^ M. Mofrad, H. Karcher, and R. Kamm, Cytoskeletal mechanics: models and measurements, 2006, 71-83

- ^ V. Lubarda and A. Marzani, Viscoelastic response of thin membranes with application to red blood cells, Acta Mechanica, 2009, 202, 1–16

- ^ D. Fedosov, B. Caswell, and G. Karniadakis, Coarse-Grained Red Blood Cell Model with Accurate Mechanical Properties, Rheology and Dynamics, 31st Annual International Conference of the IEEE EMBS, Minneapolis, Minnesota, 2009

- ^ J. Li, Z. Tang, Y. Xia, Y. Lou, and G. Li, Cell viscoelastic characterization using photoacoustic measurement, Journal of Applied Physics, 2008, 104

- ^ M. Marinkovic, K. Turner, J. Butler, J. Fredberg, and S. Suresh, Viscoelasticity of the Human Red Blood Cell, American Journal of Physiology - Cell Physiology 2007, 293, 597-605.

- ^ A. Ündar, W. Vaughn, and J. Calhoon, The effects of cardiopulmonary bypass and deep hypothermic circulatory arrest on blood viscoelasticity and cerebral blood flow in a neonatal piglet model, Perfusion 2000, 15, 121–128

- ^ S. Canic, J. Tambaca, G. Guidoboni, A. Mikelic, C Hartley, and D Rosenstrauch, Modeling Viscoelastic Behavior of Arterial Walls and their Interaction with Pulsatile Blood Flow, Journal of Applied Mathematics, 2006, 67, 164–193

- ^ J. Long, A. Undar, K. Manning, and S. Deutsch, Viscoelasticity of Pediatric Blood and its Implications for the Testing of a Pulsatile Pediatric Blood Pump, American Society of Internal Organs, 2005, 563 - 566

- ^ A. Undar and W. Vaughn, Effects of Mild Hypothermic Cardiopulmonary Bypass on Blood Viscoelasticity in Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting Patients, Artificial Organs 26(11), 964–966

- ^ K. Brookshier and J. Tarbell, Evaluation of a transparent blood analog fluid: aqueous xanthan gum/glycerin, Biorheology, 1993, 2, 107-16

- ^ G. Thurston, N. Henderson, and M. Jeng, Effects of Erythrocytapheresis Transfusion on the Viscoelasticity of Sickle Cell Blood, Clinical Hemorheology and Microcirculation 30 (2004) 61–75